Artificial Intelligence in Clinical Nutrition: Opportunities and Limits of the Digital Transformation

Artificial intelligence is transforming how physicians, dietitians, and nutritionists collect, analyze, and use patients’ dietary data. From smartphone applications that recognize food to decision-support platforms, these technologies promise to overcome the limitations of traditional paper food records and food frequency questionnaires. This transformation, however, does not occur without regulatory constraints, technical limitations, and professional responsibilities that modern clinicians cannot ignore. This article analyzes the current landscape of AI in clinical nutrition, available tools, and strategies to implement them safely and in compliance with European regulations.

Alessandro Drago

1. The digital revolution in dietary assessment

1.1 From paper records to intelligent computer vision systems

For decades, the “gold standard” of dietary assessment has relied on traditional methods: paper food diaries, 24-hour dietary recalls, and food frequency questionnaires (FFQs). These tools remain fundamental but are affected by intrinsic limitations: dependence on patient memory, social desirability bias (under-reporting of “junk food”, over-reporting of “healthy” foods), and high workload for manual data analysis.

A 2025 scoping review in Frontiers in Nutrition describes how AI-based dietary assessment tools are moving from research labs into daily clinical practice, combining computer vision, nutritional databases, and wearable sensors to semi-automatically estimate intake [Phalle & Gokhale 2025]. Other reviews confirm that image-based systems for automatic food recognition are maturing rapidly, especially for estimating energy and macronutrient intake [Zheng 2024; Chotwanvirat 2024].

Current technologies include:

smartphone applications that capture images of meals and estimate calories and nutrients

wearables that monitor chewing and eating patterns

passive monitoring systems integrating data from apps and devices

machine learning algorithms that learn from individual intake patterns

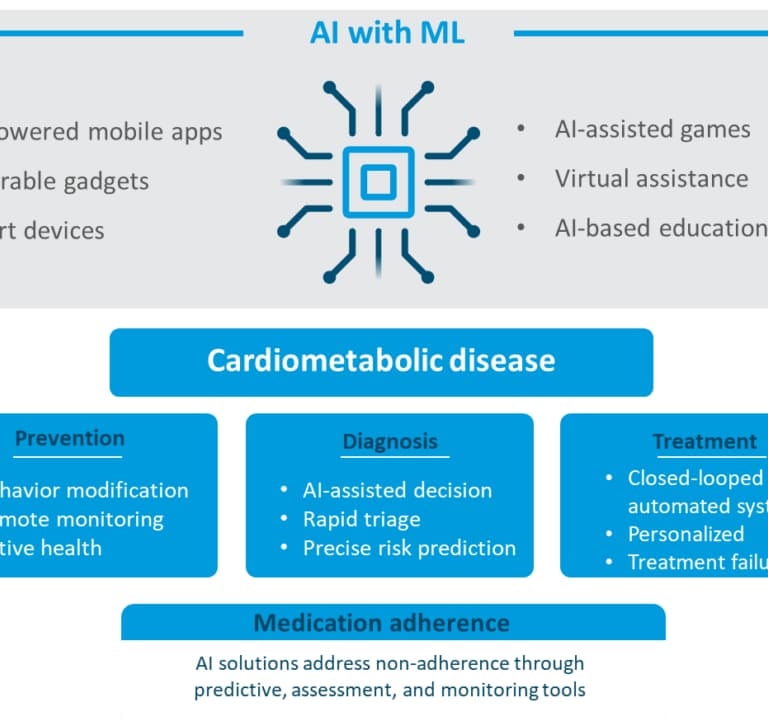

1.2 Clinical benefits, precision nutrition, and target populations

The most promising applications concern chronic disease management. In Phalle and Gokhale’s review, several trials report the usefulness of AI-assisted digital food records in patients with obesity and type 2 diabetes, where monitoring carbohydrates, energy intake, and eating patterns can support more precise therapeutic adjustments [Phalle & Gokhale 2025]. In precision nutrition, a broad scoping review shows how AI can integrate dietary, metabolic, and genetic data to personalize interventions, while stressing the need for robust clinical trials [Wu 2025].

Key target populations include:

patients with metabolic chronic conditions (type 2 diabetes, obesity)

frail older adults at risk of silent malnutrition

individuals enrolled in intensive precision nutrition programs

The promise is not just “more data”, but more granular data, collected with less burden for both patients and clinicians.

2. Current limitations and technical challenges

2.1 Heterogeneity of databases and accuracy issues

Critical reviews show that although computer vision applied to food has made major progress, important methodological limitations persist [Shonkoff 2022; Chotwanvirat 2024]. In particular:

· substantial variability across the nutritional databases used by algorithms

· differences in how foods are defined, coded, and aggregated

· limited transparency on performance metrics in real-world settings

A scoping review focusing on AI applications to measure food and nutrient intakes confirms that despite promising results, many systems have been tested in small samples or controlled environments, with few validations against objective reference methods such as doubly labelled water [Zheng 2024].

Mean caloric estimation error can still be relevant at the meal level, especially for mixed dishes, sauces, and processed foods. For this reason, the dietitian’s role in critically interpreting algorithmic outputs remains essential.

2.2 Cultural representativeness and inclusivity

An emerging issue concerns the poor representation of non‑Western cuisines in training datasets. Reviews highlight that most algorithms have been developed and validated on foods and portion sizes typical of North American or Western European contexts [Phalle & Gokhale 2025; Sosa-Holwerda 2024]. This may result in:

misrecognition of traditional or ethnic dishes

systematic under‑ or overestimation of portions

lower accuracy for populations with different dietary patterns

This is not just a technical matter, but a question of equity. If AI tools work better for some food cultures than others, existing health disparities may be reinforced.

2.3 Better data, but clinical outcomes still uncertain

Broad reviews on AI in nutrition research and food-health evidence show a clear pattern: AI improves the ability to collect, integrate, and analyze data, but evidence linking these tools directly to hard clinical outcomes (long-term glycemic control, weight maintenance, cardiovascular events) is still limited [Bailey 2024; Sosa-Holwerda 2024]. Many studies stop at intermediate endpoints (data quality, adherence to logging, user satisfaction) and do not yet demonstrate a net benefit on health outcomes.

3. AI in decision support: from LLMs to recommendation systems

3.1 Large Language Models (LLMs) and the AI Act

With the entry into force of the EU Artificial Intelligence Act (Regulation (EU) 2024/1689), AI systems intended for patient management and care, including clinical decision support (CDS) software and LLM-based tools in clinical settings, are classified as “high-risk” [Reg. EU 2024/1689]. This entails:

structured risk management and quality systems

requirements for transparency and traceability

effective human oversight (human‑in‑the‑loop)

technical documentation available to authorities

Large Language Models are already being used to:

summarize complex medical records and long reports

translate technical reports into patient-friendly language

generate tailored educational materials on diet and lifestyle

3.2 Hallucinations, bias, and AI literacy

A key review in eClinicalMedicine on AI education for clinicians introduces the notion of AI literacy, stressing that safe use of LLMs requires new skills: probabilistic interpretation of responses, bias recognition, and the ability to judge clinical plausibility [Schubert 2024]. Other papers highlight a widening gap between the commercial diffusion of advanced chatbots and clinicians’ capacity to critically appraise them [Garvey 2021; Pupic 2023].

Main risks include:

hallucinations, i.e. the generation of false but plausible information, especially when the model fills “gaps” with unsupported guesses [Schubert 2024]

training data bias, potentially skewing recommendations because of uneven guideline coverage, underrepresentation of certain groups, or non-transparent data sources [Bailey 2024]

In this context, any diet plan or supplement protocol suggested by an LLM must be cross‑checked against official guidelines and the patient’s clinical status [Labkoff 2024].

3.3 Model cards, CDS, and professional responsibility

Recent recommendations on AI‑enabled clinical decision support stress the need for transparency, explainability, and human control [Labkoff 2024]. Model cards and system labels should specify:

training datasets and their characteristics

validated populations and settings

appropriate and inappropriate use cases

For nutrition professionals, this means demanding clear documentation from AI vendors and assuming final responsibility for decisions, documenting in the record how AI was used and what its limitations are.

4. Dietary supplements and AI: claims, surveillance, and the human factor

4.1 A market at high risk of misinformation

A study by Muela-Molina and colleagues on 437 radio advertisements for food supplements in Spain found that over 80% of function claims were non‑compliant with the European regulatory framework, either unauthorized or used outside approved conditions [Muela-Molina 2021]. In such a context, using generative AI to create marketing copy or “personalized reports” risks amplifying misinformation if not properly controlled.

4.2 AI as a surveillance tool for EFSA

The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) is exploring AI through its AI@EFSA roadmap to strengthen surveillance on food safety and communication. Among the avenues considered:

natural language processing to analyze large volumes of web and social content

AI tools to detect suspicious health claims and potential fraud

support for extracting and integrating data from New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) [EFSA 2024a; EFSA 2024b; EFSA 2024c]

The same technologies that can generate misleading content can, if governed appropriately, help authorities identify and counter it.

4.3 AI‑assisted supplement recommendations and human‑in‑the‑loop protocols

In clinical settings, AI can support estimation of micronutrient needs, highlight potential nutrient–drug interactions, and help prioritize complex cases [Atwal 2024]. Nonetheless, the literature is clear: decisions about whether to prescribe a supplement, at what dose and for how long, remain clinical acts that must be framed within human‑in‑the‑loop protocols:

the algorithm proposes, based on data and models

the clinician evaluates, integrates, and if necessary modifies

final clinical responsibility remains human [Labkoff 2024; Atwal 2024]

Patients should be made aware that wellness apps and generic recommendation engines are not medical devices.

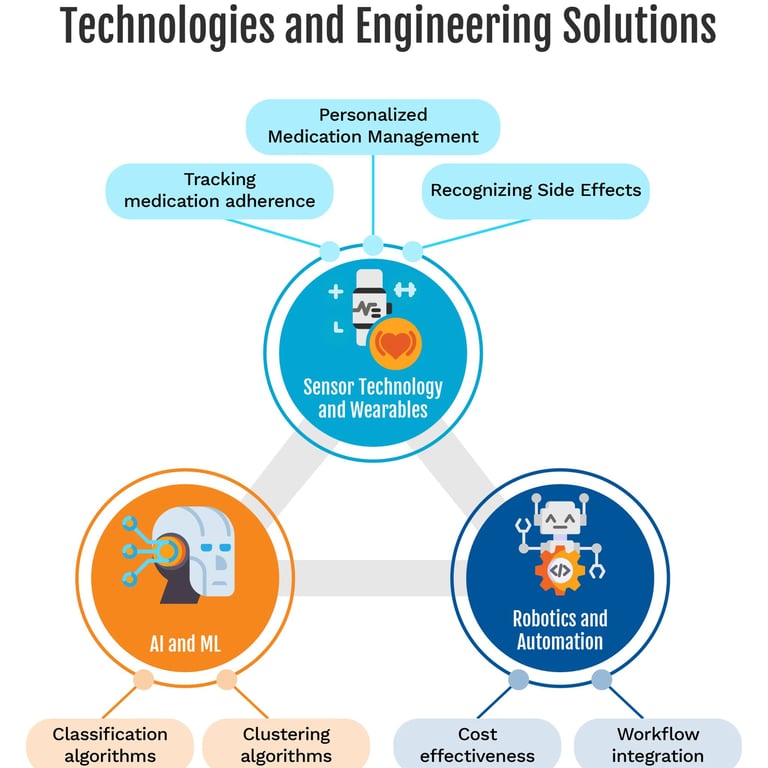

5. Adherence to therapies and supplements: what machine learning can do

5.1 Why adherence matters

Poor adherence is a major driver of therapeutic failure in chronic diseases. It worsens clinical outcomes, increases complications and hospitalizations, and raises healthcare costs. Several reviews have explored the use of AI to:

monitor medication intake

predict risk of non‑adherence

personalize support and behavioral interventions [Babel 2021; Bohlmann 2021; Rhudy 2025; Zavaleta-Monestel 2025]

5.2 Digital tools to support adherence

Documented applications include:

intelligent reminders via apps, SMS, or wearables

digital Directly Observed Therapy solutions using computer vision to confirm ingestion

passive smartphone and wearable data analysis to infer adherence patterns

chatbots and apps providing motivational coaching and responses to everyday questions [Babel 2021; Bohlmann 2021]

An updated systematic review indicates that, overall, these tools tend to improve adherence compared with usual care, while highlighting substantial heterogeneity in adherence definitions and measurement methods [Zavaleta-Monestel 2025].

5.3 Predictive models and risk stratification

A scoping review of machine learning approaches to medication non‑adherence reports good performance for models such as random forests or gradient boosting, especially when fed rich clinical and socio‑demographic data [Rhudy 2025]. In a specific study, a 5‑item questionnaire integrated into a machine learning model allowed classification of patients into low, moderate, and high‑risk clusters with 70% accuracy and a 93% negative predictive value, particularly useful to identify those unlikely to be non‑adherent [Korb-Savoldelli 2023].

For nutrition and supplements, these principles may be useful when:

supplementation is part of an evidence‑based therapeutic regimen

poor adherence carries tangible clinical risk (e.g. documented deficiency, essential supplementation)

Again, AI should be used to support adherence to appropriate, evidence‑based treatments, not to maintain unnecessary or questionable interventions.

6. Governance, ethics, and the clinician’s role

6.1 Open questions

Wide use of AI in clinical nutrition raises governance and ethical questions:

who is accountable if an algorithmic underestimation of intake leads to malnutrition or excess?

how can training datasets be made inclusive of diverse food cultures?

how can data and model bias be prevented from translating into discriminatory recommendations?

6.2 Towards common standards and transparency

Emerging responses include:

model cards documenting scope, training data, and known limitations [Schubert 2024]

reporting guidelines for clinical trials involving AI components

registries of AI tools used in healthcare, with performance and risk information [Labkoff 2024]

6.3 AI as a “third eye”, not an autopilot

The key message is that AI does not replace the therapeutic relationship; it can make it more data‑driven. For clinicians AI systems should act as a “third eye” on the data, not as a shortcut to decisions: outputs must always be checked, critiqued, and integrated with clinical context. Patients and professionals should openly discuss the benefits and limitations of digital tools being used

#NutriAI #NutriAINewsletter #ArtificialIntelligence #AI #Nutrition #ScientificCommunication #FoodTech #FoodSafety #AIRegulation #EFSA #RegulatoryCompliance #ISO42001 #HealthClaims #DigitalInnovation #ResponsibleAI #AITransparency #Governance #DataScience #FoodCompliance #DigitalNutrition #FoodLaw #HighRiskAI #TrustInAI #AINews #ScientificCommunication #EUAIAct #MedicalEducation #AIliteracy #ContinuingEducation #Dietitians #Nutritionists #LargeLanguageModels #AIAct #ClinicalDecisionSupport #DigitalHealth #Nutrition

Disclaimer: All rights to images and content used belong to their respective owners. This article is provided for educational and informational purposes only. It does not constitute legal or regulatory advice. Organizations should consult qualified legal and regulatory experts before implementing AI systems in the nutrition sector.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

Bibliographic and Regulatory References

Phalle A, Gokhale D. Navigating next‑gen nutrition care using artificial intelligence‑assisted dietary assessment tools—a scoping review of potential applications. Front Nutr. 2025;12:1518466.

Wu X, Oniani D, Shao Z, et al. A Scoping Review of Artificial Intelligence for Precision Nutrition. Adv Nutr. 2025;16(4):100398.

Zheng J, Wang J, An R. Artificial Intelligence Applications to Measure Food and Nutrient Intakes: Scoping Review. J Med Internet Res. 2024;26:e54557.

Shonkoff E, et al. The State of the Science on Artificial Intelligence‑Based Dietary Assessment Methods That Use Digital Images: A Scoping Review. Curr Dev Nutr. 2022;6(Suppl 1):534.

Chotwanvirat P, et al. Advancements in Using AI for Dietary Assessment Based on Food Images: Scoping Review. J Med Internet Res. 2024;26:e51432.

Bailey RL, et al. Artificial intelligence in food and nutrition evidence: The challenges and opportunities. PNAS Nexus. 2024;3(12):pgae461.

Sosa-Holwerda A, et al. The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Nutrition Research: A Scoping Review. Nutrients. 2024;16(13):2066.

Muela-Molina C, Perelló-Oliver S, García-Arranz A. False and misleading health‑related claims in food supplements on Spanish radio. Public Health Nutr. 2021;24(15):5156–5165.

Schubert T, Oosterlinck T, Stevens RD, et al. AI education for clinicians. eClinicalMedicine. 2024;79:102968.

Labkoff S, Oladimeji B, Kannry J, et al. Toward a responsible future: recommendations for AI‑enabled clinical decision support. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2024;31(11):2730–2739.

Atwal K. Artificial intelligence in clinical nutrition and dietetics: A brief overview of current evidence. Nutr Clin Pract. 2024;39(4):736–742.

Babel A, Taneja R, Mondello Malvestiti F, Monaco A, Donde S. Artificial Intelligence Solutions to Increase Medication Adherence in Patients With Non‑communicable Diseases. Front Digit Health. 2021;3:669869.

Bohlmann A, Mostafa J, Kumar M. Machine Learning and Medication Adherence: Scoping Review. JMIRx Med. 2021;2(4):e26993.

Rhudy C, Johnson J, Perry C, et al. Machine learning approaches to predicting medication nonadherence: a scoping review. Int J Med Inform. 2025;204:106082.

Korb‑Savoldelli V, Tran Y, Perrin G, et al. Psychometric properties of a machine learning–based patient‑reported outcome measure on medication adherence. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25:e42384.

Contact details

Follow me on LinkedIn

Nutri-AI 2025 - Alessandro Drago. All rights reserved.

e-mail: info@nutri-ai.net