Implementation of AI in Scientific Nutritional Communication: Regulatory Compliance and Best Practices in Workplace Contexts

AI represents an unprecedented transformation in the field of scientific communication and nutrition, bringing with it extraordinary opportunities and complex regulatory responsibilities. In Europe, the regulatory framework governing the implementation of AI in the health and wellness sector is based on four fundamental pillars: the EU AI Act, Regulation (EC) 1924/2006 on nutrition and health claims, the EFSA (European Food Safety Authority) guidelines, and the ISO/IEC 42001 standard for the management of AI systems.

Alessandro Drago

A New Regulatory Paradigm for AI in the Food Sector

The implementation of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in scientific and nutritional communication represents an epochal transformation that is redefining operational modalities, decision-making processes, and communication strategies in the health and wellness sector. This technological revolution brings extraordinary opportunities in terms of operational efficiency, accuracy of scientific assessments, and personalization of nutritional recommendations, while simultaneously generating regulatory responsibilities of considerable complexity that organizations must address with methodological rigor and operational transparency.

In the European context, the regulatory framework governing the adoption and implementation of AI in workplace contexts of the food and nutrition sector is articulated through four fundamental regulatory pillars, each establishing specific and complementary requirements: the European Union's Artificial Intelligence Regulation (EU AI Act, Regulation EU 2024/1689), which entered fully into force in August 2024 as the first comprehensive multinational regulatory framework for AI; Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council on nutrition and health claims made on foods, which constitutes the regulatory basis for any communication regarding health properties of foods; the scientific and operational guidelines of the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), which establish methodological standards for evaluating scientific evidence; and the international standard ISO/IEC 42001:2023, which provides a systematic framework for managing artificial intelligence systems in organizations.

This article aims to provide a technical and operational guide, scientifically grounded and verifiable, intended for organizations that intend to implement AI solutions in scientific nutritional communication, while ensuring full regulatory compliance, methodological transparency, institutional accountability, and maintenance of stakeholder trust in a rapidly evolving regulatory environment.

The European Regulatory Framework: Legal Architecture and Operational Implications

The EU AI Act: Risk-Based Regulation and System Classification

Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 of the European Parliament and of the Council, commonly referred to as the Artificial Intelligence Act, represents the cornerstone of European AI regulation. Published in the Official Journal of the European Union on July 12, 2024, and entering into force on August 1, 2024, this unprecedented regulatory framework establishes harmonized rules for the development, placing on the market, and use of AI systems in the European Union, following a risk-based approach that balances technological innovation and protection of fundamental rights.

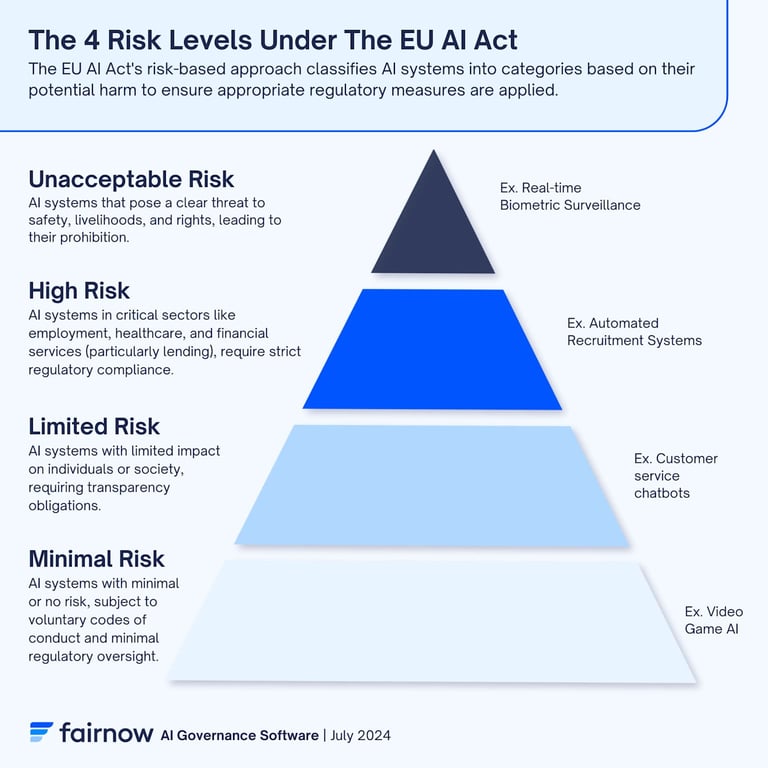

The distinctive characteristic of the EU AI Act is its risk-based methodological approach, which classifies AI systems according to four progressively increasing risk categories, each subject to regulatory obligations proportional to the potential severity of consequences for health, safety, and fundamental rights of individuals. This taxonomy includes: unacceptable risk systems, categorically prohibited because considered incompatible with the fundamental values of the European Union and potentially harmful to fundamental human rights; high-risk systems, defined in Annexes I and III of the Regulation, which have significant impact on health, safety, and fundamental rights and are subject to stringent compliance obligations; limited or medium-low risk systems, for which transparency obligations primarily apply; and minimal risk systems, which are not subject to particular regulatory obligations given their benign nature.

Regarding specifically the scientific nutritional communication sector, the applicability of the high-risk classification is particularly relevant. The majority of AI systems implemented in this field fall into the high-risk category for several technical and regulatory reasons. First, systems that generate personalized nutritional recommendations based on individual health, genetic, or metabolic profiles have direct impact on human health and therefore require qualified human supervision (human oversight) as established by Article 14 of the Regulation. Second, systems that perform automated assessments of health claims or support decision-making processes relating to regulatory compliance or food product authorization directly influence informational accuracy and consumer safety, configuring as critical systems for public health. Third, AI systems used for systematic analysis of scientific literature supporting EFSA dossiers for health claims, or for detecting documentary fraud, process sensitive data and support regulatory decisions with significant economic and public health consequences.

The Regulation establishes stringent compliance timelines that organizations must respect. February 2, 2025, marks the beginning of transparency obligations for limited-risk systems, as provided by Article 52 of the Regulation. August 2, 2026, represents the critical deadline for full compliance of high-risk systems, as established by Article 113, with all requirements of Articles 8-15 fully operational. Finally, August 2, 2027, is the final deadline for compliance of high-risk systems already integrated into regulated products before the Regulation entered into force.

Regulation (EC) 1924/2006: Regulatory Foundation for Health Claims

Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of December 20, 2006, on nutrition and health claims made on foods constitutes the fundamental pillar of European regulation regarding communication of health properties of foods. This regulatory framework, consolidated by nearly two decades of application and extensive jurisprudence of the Court of Justice of the European Union, establishes rigorous criteria to ensure that any communication regarding beneficial effects of foods on health is scientifically accurate, non-misleading, and verifiable.

The fundamental criteria that the Regulation imposes for health claims are articulated and stringent. First, statements must be based on scientific evidence generally accepted by the international scientific community and publicly available, as specified in Article 6 of the Regulation. Second, all health claims must undergo rigorous scientific evaluation conducted by EFSA through the Panel on Nutrition, Novel Foods and Food Allergens (NDA), following procedures established in Articles 15-19 of the Regulation. Third, authorized claims must be used exactly according to approved formulations published in the EU Register of nutrition and health claims, publicly accessible on the European Commission's online platform. Finally, health claims must be supported by robust scientific data, preferably derived from randomized controlled clinical trials on human populations, as specified in EFSA guidelines on scientific substantiation.

The implications of this regulatory framework for AI systems operating in nutritional communication are profound and multidimensional. Any AI system that generates, selects, validates, or communicates health claims must be designed and validated to ensure complete scientific traceability, linking every generated statement to supporting scientific data present in peer-reviewed and verifiable literature. The system must also incorporate automated compliance mechanisms that verify in real-time compliance with exact formulations authorized by EFSA and present in the EU Register. It is imperative to maintain a complete documentary audit trail of every algorithmic decision, the scientific basis used, and the human validation process applied. Finally, systems must be designed with intrinsic mechanisms for exclusion of algorithmic bias to systematically avoid distortions in training data or decision logic leading to generation of scientifically unsupported or potentially misleading statements to consumers.

EFSA Guidelines: Scientific Excellence and Human-Centric AI

The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) has developed in recent years a strategic approach to integrating artificial intelligence into its scientific assessment processes, culminating in the publication of the AI Roadmap Vision 2027 and a series of technical documents outlining best practices and operational principles. This approach is based on rigorous methodological standards that balance operational efficiency and scientific integrity, establishing a paradigmatic model for responsible implementation of AI in food and nutritional risk assessment contexts.

EFSA's approach to AI is articulated on three interconnected conceptual and operational pillars. The first pillar concerns the development of advanced semantic ontologies and Big Data infrastructures for structured management of scientific evidence. EFSA has invested significantly in developing the FoodEx2 Exposure Hierarchy, a complex ontology for food classification, and knowledge graph systems that enable advanced semantic querying of scientific literature. These systems allow standardized cataloging of evidence, more efficient search of pertinent literature, and more accurate assessment of methodological quality of scientific studies.

The second pillar consists of implementing AI governance frameworks that ensure rigorous validation and qualified human supervision of all automated processes. EFSA has established that any output generated by AI systems must undergo validation against human gold standards before being incorporated into official scientific assessments or used to support regulatory decisions. This approach ensures that automation does not compromise scientific quality and that any algorithmic errors are identified and corrected before they can influence risk assessment decisions.

The third pillar is represented by the principle of human-centric AI, according to which artificial intelligence must be conceived as a tool for amplifying human capabilities rather than replacing scientific expertise. This principle translates operationally into designing AI systems that support but do not replace scientific experts, providing tools for initial screening, automated synthesis of evidence, and identification of patterns in data, while always maintaining final decision control in the hands of qualified experts.

The practical implications of this approach for private sector organizations are significant. Automated scientific research through AI, as in the case of systematic reviews or algorithm-assisted meta-analyses, must maintain rigorous validation against human standards comparable with traditional methodologies. Systems must be designed to identify and signal potential methodological bias in analyzed studies, using validated checklists such as the GRADE tool (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations). Finally, every output must be accompanied by transparent documentation specifying which processes were automated, which human validations were applied, and what are the methodological limits and residual uncertainty of conclusions.

ISO/IEC 42001:2023: Systematic and Governed AI Systems Management

The international standard ISO/IEC 42001:2023 "Information technology — Artificial intelligence — Management system," officially published on December 18, 2023, by the International Organization for Standardization and the International Electrotechnical Commission, represents the first globally certifiable standard for managing artificial intelligence systems in organizations. This regulatory framework provides a comprehensive methodological structure for implementing, maintaining, and continuously improving an AI management system (AIMS) that is aligned with regulatory, ethical, and operational requirements.

The structure of ISO/IEC 42001 standard follows the High-Level Structure (HLS) model common to all ISO management system standards, facilitating integration with other standards such as ISO 9001 (Quality Management), ISO 27001 (Information Security Management), and ISO/IEC 27701 (Privacy Information Management). The framework is articulated in ten main clauses covering the entire lifecycle of the management system.

Clause 4 (Context of the organization) requires organizations to determine external and internal issues relevant to the AI management system, including analysis of needs and expectations of interested parties, identification of applicable legal and regulatory requirements (including EU AI Act, GDPR, and specific sectoral regulations), and definition of scope and boundaries of the AI management system in relation to strategic organizational objectives.

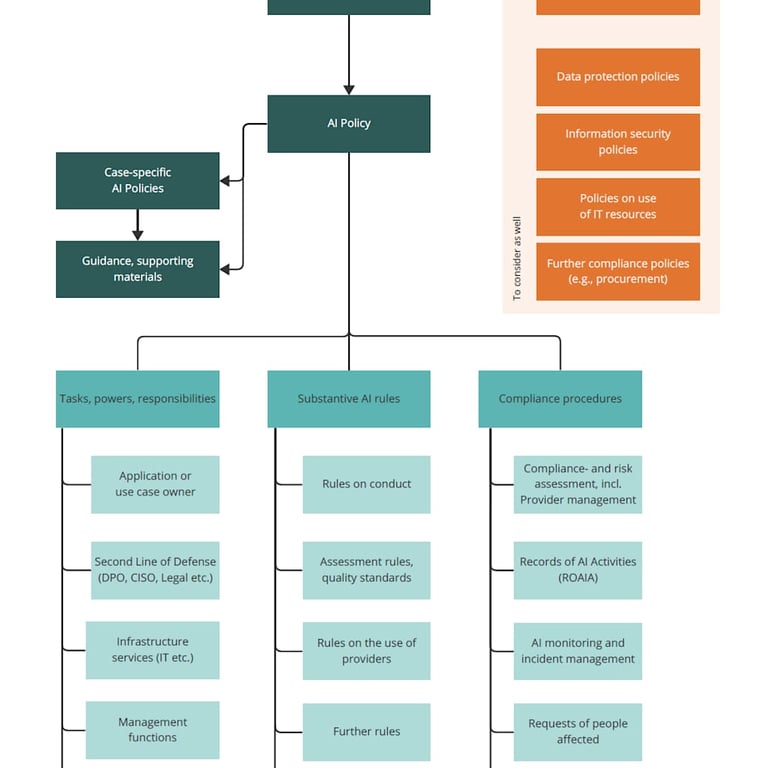

Clause 5 (Leadership) establishes governance requirements, requiring explicit commitment from top management, definition of a documented AI policy articulating organizational principles for responsible AI use, and assignment of clear roles, responsibilities, and authorities for all aspects of the AI management system. This clause is particularly critical for ensuring organizational accountability.

Clause 6 (Planning) requires a systematic approach to assessing risks and opportunities associated with AI, defining measurable objectives for the AI management system, and planning actions to achieve these objectives. In the nutritional context, this planning must incorporate specific assessment of risks to human health, food safety, and scientific accuracy of generated communications.

Clauses 7 and 8 (Support and Operational activities) detail requirements for competent human resources, adequate technological infrastructure, document management processes, operational controls throughout the entire AI systems lifecycle (from design through deployment to decommissioning), and supply chain management for externally developed AI components.

Clauses 9 and 10 (Performance evaluation and Improvement) establish requirements for continuous monitoring, internal audits, management review, and management of non-conformities through corrective actions and continuous system improvement.

For organizations in the nutritional sector, implementation of ISO/IEC 42001 provides a structured framework for aligning AI systems with the multiple and often complex requirements of the EU AI Act, GDPR (EU Regulation 2016/679 on personal data protection), and specific sectoral regulations such as Regulation 1924/2006 and Regulation (EU) 2015/2283 on novel foods.

Risk Assessment and Classification of AI Systems in the Nutritional Sector

Risk Assessment Methodology Compliant with EU AI Act

Accurate assessment of the risk level of each AI system according to the EU AI Act taxonomy constitutes the fundamental and essential phase of any compliant implementation process. This assessment must follow a structured methodology that simultaneously considers multiple dimensions: potential impact on individual health and safety, degree of decision-making automation, sensitivity of processed data, system usage context, and potential consequences of malfunctions or erroneous decisions.

The classification process must be conducted through systematic analysis guided by specific diagnostic questions. First, it is necessary to determine whether the system generates recommendations or decisions that directly impact human health or safety. In the nutritional context, this question is particularly relevant for systems providing personalized dietary advice, validating health-related claims, or supporting nutritional therapeutic decisions. Second, it is necessary to assess whether the system influences decisions concerning regulatory compliance, food product authorization, or health claims validation, as such decisions have significant regulatory and commercial consequences. Third, it must be ascertained whether the system processes sensitive personal data as defined by Article 9 of GDPR, including health, genetic, biometric data, or data relating to individual health conditions. Fourth, it is necessary to assess whether system outputs could, in case of errors or malfunctions, constitute violations of fundamental rights, generate risks to food safety, or produce misleading information for consumers. Finally, it must be determined whether the system integrates data from external sources not directly controlled by the organization, introducing potential vulnerabilities in terms of data quality, accuracy, and reliability.

If the answer to one or more of these diagnostic questions is affirmative, the system must be presumptively classified as high-risk according to Annex III of the EU AI Act, and consequently subject to all stringent obligations established in Title III, Chapter 2 of the Regulation (Articles 8-15), including requirements for quality management system, data governance, technical documentation, record-keeping, transparency, human oversight, accuracy, robustness, and cybersecurity.

In the specific context of scientific nutritional communication, several types of systems typically fall into the high-risk category with a high degree of certainty. Systems generating personalized nutritional recommendations based on individual health, genetic, or metabolic profiles are classified high-risk due to direct impact on human health and the essential need for qualified human oversight. Automated health claims validation systems that verify compliance of proposed statements against the authorized EFSA database are high-risk because they support regulatory decisions with significant commercial consequences and potential for generating misleading claims in case of error. Systematic scientific literature analysis systems used to identify and synthesize evidence supporting health claims submission to EFSA are high-risk because they directly impact authorization decisions with public health consequences. Fraud detection systems applied to technical documentation in authorization dossiers are high-risk due to access to sensitive commercial data and impact on regulatory compliance processes. Finally, computer vision-based quality control systems for automated inspection of food labels and verification of compliance of reported statements are high-risk due to direct impact on food safety and compliance of information provided to consumers.

Operational Compliance Requirements for High-Risk Systems

Quality Management System: Structure and Documentation

Article 17 of the EU AI Act establishes detailed requirements for implementing a robust and documented Quality Management System (QMS) for all providers of high-risk AI systems. This QMS must be proportionate to organization size but comprehensive in its essential elements, covering the entire AI system lifecycle from initial design through development, validation, deployment, post-market monitoring to eventual decommissioning.

The QMS must mandatorily include a documented risk management system compliant with Article 9 of the Regulation, which provides for systematic identification and cataloging of all reasonably foreseeable risks associated with intended use and reasonably foreseeable but improper use of the system. This identification must consider risks to health and safety, risks to fundamental rights (including privacy, non-discrimination, fairness), and operational risks. For each identified risk, the QMS must document quantitative or qualitative assessment of occurrence probability and potential severity of consequences, using validated methodologies such as ISO 31000 risk matrix or FMEA (Failure Mode and Effects Analysis). Mitigation measures implemented to reduce risks to acceptable levels, validations of such measures' effectiveness, and residual risks remaining after mitigation implementation must also be documented.

The QMS must establish and document rigorous procedures for collection, processing, and validation of data used for training, validation, and testing of AI systems, as required by Article 10 of the Regulation. These procedures must ensure that datasets are relevant, representative, free from significant errors, and complete with respect to target population characteristics. In the nutritional context, this implies ensuring that data include adequate representation of diverse geographical populations, ethnic groups, age ranges, health conditions, and dietary patterns, to avoid systematic bias that could lead to inadequate recommendations for specific subpopulations.

Technical documentation required by Article 11 and detailed in Annex IV of the Regulation must provide comprehensive system description, including: overall architecture and main components; algorithms and machine learning techniques used; training, validation, and testing datasets with details on composition, sources, collection methodologies, and preprocessing; performance metrics and validation results; known system limitations and operational conditions for which the system was validated; risk analysis and mitigation measures; human oversight procedures implemented; cybersecurity and data protection measures.

The record-keeping and logging system required by Article 12 must ensure automatic traceability of all system decisions through time-stamped recording of all inputs received, all outputs generated, all relevant intermediate algorithmic decisions, all human override or validation interventions, and all identified anomalous events or malfunctions.

Transparency, User Information, and AI Nutrition Labels

Article 13 of the EU AI Act imposes stringent transparency obligations for high-risk systems, requiring deployers to provide clear, understandable, and accessible information to individuals interacting with the system or subject to its decisions. In the context of scientific nutritional communication, these obligations translate into specific requirements for informing consumers, healthcare professionals, and regulatory authorities.

Information provided must be accessible and understandable to diverse audiences without requiring specialized technical background, using clear, unambiguous language appropriate to the expected user's comprehension level. It must be explicitly and prominently communicated that information, recommendations, or decisions are generated or supported by an artificial intelligence system, clearly distinguishing between purely algorithmic assessments and expert-validated human assessments. Consumers and authorities must have the possibility to understand, at an appropriate level of detail, how the system reached a specific conclusion or recommendation, what data were considered, and what decision logic was applied. Finally, information must explicitly state the system's capabilities and limits, avoiding exaggerated performance claims and specifying operational conditions for which the system was validated.

A practical approach to satisfying these transparency requirements in the nutritional sector is represented by implementing "AI Nutrition Labels" or "Model Cards," conceptually analogous to nutritional labels on food products. These structured disclosure tools should document in standardized and easily accessible format: provenance and quality of data used by the system (for example, "peer-reviewed literature indexed in PubMed and EFSA database"), specifying temporal coverage dates and quality assurance methodologies applied; algorithmic methodologies used in non-technical terms (for example, "automated semantic comparison of proposed ingredients against EFSA lists of authorized substances, with defined matching thresholds"); bias mitigation measures implemented, specifying which populations and conditions were included in fairness testing (for example, "system tested for performance equity across 15 diverse demographic groups by age, gender, and ethnicity"); validation approach used and performance metrics obtained (for example, "95% agreement with qualified human expert assessments on test dataset of 1000 cases"); nature and timing of human oversight in the process (for example, "every health claim generated is reviewed by EFSA-qualified nutritionist before publication"); explicit system limitations and inappropriate uses to avoid (for example, "the system does not provide medical advice for diagnosed pathological conditions and does not replace assessment by qualified healthcare professionals").

Human Oversight: Implementation Models and Best Practices

Article 14 of the EU AI Act establishes that high-risk AI systems must be designed and developed to enable effective human supervision during their use. This fundamental requirement is based on the principle that decisions with significant impact on people's lives cannot be delegated entirely to automated systems without possibility of intervention, control, and override by competent and responsible human beings.

The Regulation identifies three main modes of human oversight, each appropriate for different usage contexts and risk levels. The Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) model provides that the system generates recommendations or decision proposals that must be explicitly approved by a competent human operator before execution or communication to end recipients. This model is appropriate for decisions with high impact on health or safety, such as health claims validation before publication, generation of personalized therapeutic nutritional recommendations, or approval of food product formulation changes. Effective HITL implementation requires designing user interfaces that clearly present system recommendations together with information relevant for assessment (supporting scientific evidence, confidence level, factors considered), require explicit approval or rejection action, and record human decision with motivations when pertinent. Personnel exercising HITL supervision must possess specific competencies in the application domain (for example, qualified dietitians, nutritionists, or food scientists) and receive adequate training on system capabilities and limitations.

The Human-on-the-Loop (HOTL) model provides human supervision with intervention capacity at any time, but the system operates autonomously within predefined parameters and under continuous monitoring. This model is appropriate for medium-impact systems where complete automation provides significant efficiency benefits but the possibility of human intervention for anomalous cases or unforeseen situations remains necessary. An application example in the nutritional sector is automated screening of technical documentation for completeness and formal compliance, with alerts to human operators when anomalies requiring in-depth investigation are identified. HOTL implementation requires monitoring dashboards that visualize in real-time system activities, decisions made, and performance indicators, with automatic alert mechanisms for situations requiring human attention (for example, statistical anomalies, low system confidence cases, or borderline decisions).

The Human-in-Command (HIC) model maintains complete strategic and tactical control in human operators' hands, with AI providing decision support but not operational autonomy. This model is appropriate for critical decisions impacting fundamental regulatory compliance, food safety, or fundamental rights, such as final approval of health claims submission to EFSA, product recall decisions, or significant production process changes with safety implications. Implementation requires workflows where AI provides analysis, synthesis, and recommendations that inform but do not bind final human decision, with complete traceability of human decision process and its motivations.

For nutritional communication systems, the HITL model is generally required and considered best practice for any process generating health claims, nutritional recommendations with potential health impact, or information intended to guide food choices with health relevance. Transition toward HOTL or HIC models should be considered only after robust demonstration of system reliability through extended periods of operation under HITL supervision, with complete documentation of performance and absence of critical errors.

Post-Market Monitoring and Continuous Compliance

Article 72 of the EU AI Act introduces the obligation of post-market monitoring for providers of high-risk systems, requiring establishment of systems for active and systematic collection of information on experience acquired from use of AI systems after their placing on the market or putting into service, to promptly identify emerging risks and needs for corrective actions.

The post-market monitoring system must be proportionate to the nature of the AI system and risks it poses, but must mandatorily include several functional components. First, a data collection system that systematically tracks interactions between system and users, recording typology and frequency of requests, usage patterns, actual operational contexts (which could differ from those initially predicted), and explicit user feedback. Second, a performance evaluation system that continuously verifies that the system maintains in real deployment the accuracy, precision, recall, and other KPI standards established during validation, with particular attention to identifying performance degradation over time or for specific use cases. Third, an incident reporting system compliant with Article 73 of the Regulation, which documents all malfunctions, significant errors, anomalous situations, and violations of safety or compliance requirements, with procedures for timely notification to competent authorities when required. Fourth, cyclical audit processes with frequency appropriate to risk level (for example, annually for high-risk systems in nutritional communication) to assess continuous compliance with all applicable requirements. Finally, documented change management procedures ensuring that any system update (including model retraining, algorithm modifications, or functionality extension) is subject to risk assessment, validation, and formal approval before deployment.

Deployers of high-risk systems must be prepared to demonstrate, upon request by market surveillance authorities, continuous compliance throughout system operation through complete and verifiable documentation of monitoring processes and obtained results. This documentation must be maintained for a period of at least 10 years from the system's date of placing on the market, as required by Article 18 of the Regulation.

Integration with EFSA Framework and Regulation 1924/2006: Operational Compliance

Alignment of AI-Generated Communication with EFSA Databases

A crucial requirement for compliance of AI systems in the nutritional sector is that any communication on health properties of foods generated or supported by AI must be completely aligned with official databases and EFSA scientific guidelines. This alignment requires implementation of specific technical mechanisms and organizational processes.

First, systems must integrate an automatic cross-referencing module that verifies in real-time against the EU Register of nutrition and health claims, maintained by the European Commission and publicly accessible. This register contains all authorized health claims with their exact formulations, conditions of use, any restrictions, and target populations. The AI system must verify that any proposed or generated health claim corresponds exactly to an authorized entry in the register, with matching not only on semantic content but also on exact literal formulation, as even minor variations could alter scientific meaning or be considered non-compliant by authorities.

Second, systems must verify that referenced nutritional elements (vitamins, minerals, other substances) and their quantities are based on Dietary Reference Values (DRV) established by EFSA and published in a series of Scientific Opinions of the NDA Panel between 2015 and 2017. These DRV represent reference values for nutrient intake in the European population and constitute the basis for any claim related to contributing to satisfying nutritional requirements.

Third, for products containing novel foods or novel food ingredients, systems must verify authorization in the Union List of Novel Foods established and periodically updated in compliance with Regulation (EU) 2015/2283. Only ingredients present in this list or significantly used in the EU before May 15, 1997, can be marketed, and any communication on such ingredients must respect conditions of use specified in the authorization.

Finally, systems must verify compliance with general composition and labeling requirements established in Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 on the provision of food information to consumers, ensuring that generated information is accurate, non-misleading, verifiable, and presented in a comprehensible manner for consumers.

Technical implementation of these cross-referencing mechanisms requires integration of regularly updated structured databases (EFSA and Commission lists are periodically updated with new authorizations), advanced semantic matching algorithms capable of managing linguistic variations and synonyms while maintaining fidelity to authorized formulations, and alert systems notifying operators when potential non-compliances requiring in-depth human review are identified.

Scientifically and Reproducibility of AI-Assisted Assessments

When AI systems are used to support assessment of scientific substantiation of health claims, as in the case of AI-assisted systematic reviews of scientific literature, stringent controls must be implemented to ensure that methodological rigor and reproducibility standards are equivalent or superior to those of assessments conducted manually by human experts.

EFSA guidelines for scientific substantiation of health claims, published in 2011 and updated in 2016 with specific focus on requirements for clinical studies, establish rigorous methodological criteria that any scientific evidence must satisfy to be considered appropriate to support a health claim. These criteria include an evidence hierarchy in which studies on human populations (particularly randomized controlled trials) are prioritized over in vitro or animal model studies. Rigorous assessment of methodological quality of each considered study is also required, using standardized tools for risk of bias assessment such as the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool for RCTs or ROBINS-I for observational studies. Assessment of overall consistency of scientific evidence in supporting the cause-effect relationship between substance consumption and declared health effect is necessary, considering consistency of results across different studies, dose-response relationship, and biological plausibility based on knowledge of action mechanisms.

AI systems used to conduct systematic reviews must be validated against human gold standards to ensure they do not introduce systematic bias in identification of relevant studies (for example, through incomplete search strategies or poorly formulated queries), selection of studies to include (avoiding both false positives and false negatives relative to inclusion/exclusion criteria), data extraction from studies (guaranteeing complete accuracy of extracted information), assessment of methodological quality (correctly applying standardized risk of bias assessment tools), or synthesis of evidence (avoiding conclusions unsupported by totality of evidence).

Validation must include comparison with systematic reviews conducted manually by experts following recognized methodological standards such as Cochrane standards, with quantitative agreement metrics (for example, kappa statistics for inter-rater reliability), and transparent documentation of any identified discrepancy with root cause analysis. Only after robust demonstration of equivalence or superiority to human standards can AI systems be considered reliable for use in regulatory contexts.

Practical Implementation: Operational Roadmap for Organizations

Phase 1: Initial Assessment and Gap Analysis (Months 0-3)

The initial assessment phase constitutes the essential foundation for any compliant AI systems implementation project in scientific nutritional communication. This phase must be conducted with methodological rigor and cross-functional involvement of diverse competencies to ensure complete understanding of current state and applicable regulatory requirements.

The first critical activity is creating an exhaustive AI System Inventory that maps all artificial intelligence systems currently in use in the organization or planned for future deployment. This inventory must document for each system: functional description and purpose of use; technologies and algorithms used; processed data (typology, sensitivity, volumes); users and recipients of outputs; operational context and deployment environment; criticality for business processes and potential impact on external stakeholders. Particular attention must be dedicated to identifying systems that might not be immediately recognized as "AI" by the organization but technically fall within the definition of Article 3 of the EU AI Act, such as recommendation engines, rule-based expert systems, or advanced analytics tools.

The second activity is Risk Classification of each identified system according to EU AI Act taxonomy. This classification must apply the risk assessment methodology described previously, determining for each system whether it falls into unacceptable risk, high-risk, limited risk, or minimal risk categories. For high-risk systems, detailed analysis of specific applicable requirements based on Annex III of the Regulation and system characteristics must be conducted.

The third activity is Gap Analysis comparing current state of each high-risk system with applicable regulatory requirements, identifying discrepancies and non-compliance areas. This analysis must consider all aspects of the regulatory framework: data quality and governance, technical documentation, transparency and user information, human oversight, accuracy and robustness, cybersecurity, post-market monitoring, and conformity assessment. For each identified gap, severity must be assessed (critical, high, medium, low) based on non-compliance risk and potential consequences.

The fourth activity is Stakeholder Mapping identifying all internal teams that must be involved in the compliance project (typically Legal/Compliance, IT/Data Science, Quality Assurance, Scientific Affairs, and Business Units owning the systems) and defining roles, responsibilities, and collaboration modalities.

The output of this phase is a comprehensive Assessment Report documenting complete system inventory, risk classification, identified gaps with prioritization, and high-level plan for subsequent phases. This document provides the informational basis for investment decisions and compliance project planning.

Phases 2-5: Governance, Technical Implementation, Validation, Deployment

Subsequent phases of the implementation process follow a logical progression from establishment of organizational governance, through technical implementation of necessary controls and capabilities, to complete system validation, to operational deployment with continuous monitoring. For brevity reasons, these phases are here synthesized in their essential elements, referring to technical documentation cited in references for implementation details.

Phase 2 of Governance Setup establishes necessary organizational structures and policy frameworks, including constitution of an AI Governance Committee with cross-functional representation, development of an AI Policy articulating principles and requirements, implementation of a Data Governance Framework with clear RACI roles, and definition of standardized Risk Assessment Protocols.

Phase 3 of Technical Implementation realizes technical capabilities necessary for high-risk systems compliance, implementing documented Quality Management Systems, automated Data Validation Pipelines, interfaces for effective Human Oversight, comprehensive Audit Trail Logging systems, and dashboards for continuous Performance Monitoring.

Phase 4 of Validation and Testing verifies system compliance and adequacy through Scientific Validation against gold standards, Bias Testing on diverse populations, Scenario Testing for edge cases and failure modes, consultation with competent regulatory authorities, and Pilot Deployment with intensive monitoring.

Phase 5 of Deployment and Post-Market Monitoring establishes steady-state operations with Full Deployment of validated systems, User Training for all involved personnel, operational Incident Management procedures, Continuous Improvement cycles based on feedback and monitoring, and maintenance of updated Regulatory Documentation for authority inspection.

Conclusions: Toward a Future of Responsible and Trustworthy Nutritional AI

Implementation of artificial intelligence in scientific nutritional communication represents not a dichotomy between technological innovation and regulatory compliance, but rather a strategic opportunity to combine AI's transformative potential with the highest standards of scientific integrity, consumer protection, and institutional accountability. Organizations that successfully navigate this complex landscape — those that implement AI in genuinely responsible, transparent, and well-governed ways — not only avoid regulatory and reputational risks but acquire sustainable competitive advantage based on stakeholder trust, an increasingly differentiating element in a market characterized by growing skepticism toward digital technologies and demand for transparency.

The European regulatory framework, though complex and sometimes burdensome, provides organizations with a clear roadmap for responsible implementation. The EU AI Act, Regulation 1924/2006, EFSA guidelines, and ISO/IEC 42001 standard form a coherent regulatory ecosystem that, if adequately understood and implemented, allows combining innovation and compliance, operational efficiency and scientific rigor, automation and human oversight.

For the nutrition and wellness sector, the era of responsible AI does not constitute a threat to competitiveness but an opportunity to better serve consumers through more accurate and personalized recommendations, to accelerate innovation through more efficient R&D processes, and to build lasting trust through transparency and accountability. Organizations that proactively embrace this challenge, investing in competencies, processes, and technologies necessary for compliance, will be positioned as trusted sector leaders in decades to come.

#NutriAI #NutriAINewsletter #ArtificialIntelligence #AI #Nutrition #ScientificCommunication #FoodTech #FoodSafety #AIGovernance #EUAIAct #EFSA #Compliance #ISO42001 #HealthClaims #DigitalInnovation #ResponsibleAI #Transparency #DataGovernance #FoodRegulation #HighRiskAI #TrustInAI #NutriAI #FoodLaw #AICompliance #NutritionSector

Disclaimer: All rights to images and content used belong to their respective owners. This article is provided for educational and informational purposes only. It does not constitute legal or regulatory advice. Organizations should consult qualified legal and regulatory experts before implementing AI systems in the nutrition sector.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

Bibliographic and Regulatory References

European Union. (2024). Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 June 2024 laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence and amending Regulations (EC) No 300/2008, (EU) No 167/2013, (EU) No 168/2013, (EU) 2018/858, (EU) 2018/1139 and (EU) 2019/2144 and Directives 2014/90/EU, (EU) 2016/797 and (EU) 2020/1828 (Artificial Intelligence Act). Official Journal of the European Union, L 1689/1, 12 July 2024.

European Commission. (2006). Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 December 2006 on nutrition and health claims made on foods. Official Journal of the European Union, L 404/9, 30 December 2006. Consolidated version available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:02006R1924-20141213

European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). (2024). AI@EFSA: Artificial Intelligence at EFSA. EFSA Corporate Publications. Available at: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/corporate-pubs/aiefsa

European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), (2024). Ontology roadmapping and case study implementation. EFSA Journal, 22(11):e221201. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2024.e221201

European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), (2022). Roadmap for action on Artificial Intelligence (AI) for evidence management in risk assessment: from the project More Knowledge for Better Food (KNOW4Food). EFSA Supporting Publications, 19(5):EN-7339. doi: 10.2903/sp.efsa.2022.EN-7339

European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) NDA Panel. (2017). General scientific guidance for stakeholders on health claim applications. EFSA Journal, 15(1):4680. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2017.4680. Available at: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/efsajournal/pub/4680

European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). (2025). Symposium on Data Readiness for Artificial Intelligence. EFSA Supporting Publications, EN-9434. doi: 10.2903/sp.efsa.2025.EN-9434

International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC). (2023). ISO/IEC 42001:2023 Information technology — Artificial intelligence — Management system. ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 42. First edition 2023-12-18. Available at: https://www.iso.org/standard/81230.html

European Union. (2016). Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data (General Data Protection Regulation). Official Journal of the European Union, L 119/1, 4 May 2016.

European Union. (2015). Regulation (EU) 2015/2283 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 November 2015 on novel foods. Official Journal of the European Union, L 327/1, 11 December 2015.

European Union. (2011). Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2011 on the provision of food information to consumers. Official Journal of the European Union, L 304/18, 22 November 2011.

Federation of European Risk Management Associations (FERMA). (2024). EU Policy Note on the Artificial Intelligence Act: Risk Management Implications. Brussels: FERMA. Available at: https://www.ferma.eu/publications/

AZTI Technology Centre. (2025). Ethics in Artificial Intelligence for Food and Health: Guidelines for Responsible Implementation. San Sebastián: AZTI. Available at: https://www.azti.es/en/ethics-in-artificial-intelligence-for-food-and-health/

European Commission. (2024). EU Register on nutrition and health claims. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/food/safety/labelling_nutrition/claims/register/public/

Contact details

Follow me on LinkedIn

Nutri-AI 2025 - Alessandro Drago. All rights reserved.

e-mail: info@nutri-ai.net